2. A SEQUEL TO THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN. PREFACE.

TRAVELS OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN

|

2. A SEQUEL TO THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN. PREFACE.

|

|

Der Text folgt der Ausgabe

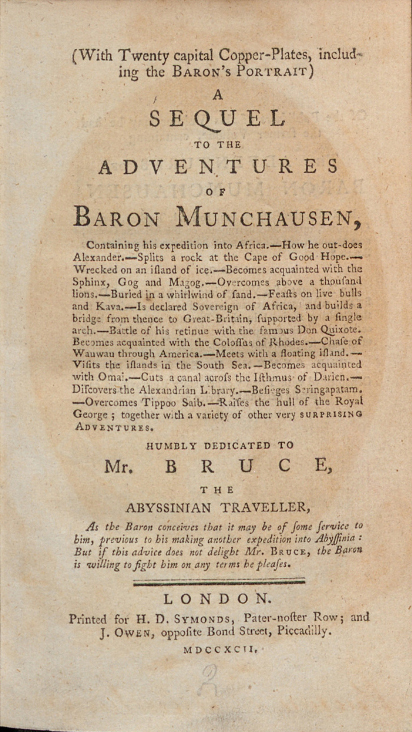

A/ SEQUEL/ TO THE/ ADVENTURES/ OF/ BARON MUNCHAUSEN, […] HUMBLY DEDICATED TO/ Mr. BRUCE,/ THE /ABYSSINIAN TRAVELLER,/ As the Baron conceives that it may be of some service to him making another expedition into Abyssinia; but if this does not delight Mr Bruce, the Baron is willing to fight him on any terms he pleases./ LONDON./ Printed for H. D. SYMONDS, Paternoster Row; and J. OWEN, opposite Bond Street, Piccadilly. MDCCXCII.| (With Twenty capital Copper-Plates, includ-/ing th BARONʼS PORTRAIT). (1792)

Übernahmen aus dem Kommentar zu G. A. Bürger: Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande. London 1788 werden nachgewiesen als Bürger 1788 mit Angabe des Kapitels. Die Hinweise in den Anmerkungen zur deutschen Übersetzung von Raspes Munchausen (Howald/Wiebel 2015) wurden dankbar verwendet.

Zu den Abkürzungen siehe das Kapitel Textgrundlagen und Kommentar.

Zu den Original-Illustrationen vergl. die Kapitel Illustrationen (Raspe/Bürger 1) und (Raspe/Bürger 2)

.jpg)

Humbly dedicated to Mr. Bruce, the Abyssinian traveller, As the Baron conceives that it may be of some service to him, previous to his making another journey into Abyssinia: But if this advice does not delight Mr. Bruce, the Baron is willing to fight him on any terms he pleases.

James Bruce of Kinnaird (1730-1794) war ein schottischer Naturwissenschaftler

und Reisender. Sein offizielles botanisches Autorenkürzel lautet „Bruce“. James

Bruce war eine auffällige Erscheinung (1,93 m). Er sprach elf Sprachen, war

Geograph, Astronom, Historiker, Linguist, Botaniker, Ornithologe und Kartograph.

Auch in der Medizin kannte er sich aus.

Wikipedia

Pompeo Batoni: James Bruce of Kinnaird. Öl auf Leinwand 1762

Ruth P. Dawson: Rudolf Erich Raspe and the Munchausen Tales (3)

The sequel, written three years after the last enlarged edition, is different. It moralizes frequently, parodies literary styles (Sterne 94—97, 139—40, Cervantes, 133—34), tends to be cruel, and refers more often to current events. But the sequel also contains some of the same motifs again: special food plants (107), a reference to Cornwall (107), someone who escapes after being swallowed alive at sea (111), and many balloons (102, 122, 143, 145). Strangely, the sequel was published by a different firm, H. D. Symonds, instead of Kearsley. Raspe was never particularly faithful to any single publisher, and for him presumably money would have decided who received the last installment.

Despite the weakness of the continuations, and especially of the sequel, the whole conglomeration has become so populär that both of the best editors of the tales, Seccombe and Carswell, reprint all of it (though from different editions and each stressing to the reader the sections regarded as authentic). Even Angelita von Münchhausen, who claims the stories as the work of her ancestor and allows Raspe only the role of scribe, reluctantly includes in her edition along with the stories that can "accurately be attributed" to Hieronymus a separate selection of the rest, "written by various hands to capitalize on the Baron's fame."24 Unlike Angelita von Münchhausen, the three main Munchausen scholars, Carswell, Seccombe, and Wackermann, seem to have the laudable intent of preserving for Raspe only what they consider best in the volume. Still, nothing prevents the argument that the talented German could write in different styles, particularly when satirizing precisely the kinds of literature he so skillfully translated. Indeed, writing in different hands fits perfectly with Raspe's talent. By the time Munchausen continuations were appearing he had already worked on a wide ränge of books from Ossian to the Laws of the Gentoos, which he rendered into German, and from scientific travel books to Lessing's "Nathan the Wise," which he translated from German into English. Small wonder if the man who contemplated writing "Unphilosophical Transactions" to lampoon the Royal Society25 turned to mimicry and mockery in Munchausen.

But the most convincing reason to decide positively that the enlarging pen was Raspe's is basically simple: allusions occur throughout the Munchausen continuations to events and interests related to him. In fact, these allusions are first noticeable in the sea adventures, not in the original hunting stories of which he is the undisputed author, or—allowing for the special role of Hieronymus—editor. Since the controversial authorship of the enlarged editions is at issue here, all the following analysis, unless otherwise noted, refers to evidence in the continuations that began appearing in the third edition.

While the new stories in the enlarged editions refer frequently to current events and broadly popular topics, these are often items which we know intrigued Raspe. Thus it is worth noting that the frequent mentioning of Captain Cook (60, 68, 82, 103, 117, 152) corresponds with an interest Raspe had cultivated almost since the moment he arrived in England. During part of the calamitous first years in London Raspe lived with Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg, German naturalists who had accompanied Cook on his second circumnavigation of the globe. Raspe helped Georg translate his masterful Voyage round the World into German.26 Raspe knew Sir Joseph Banks, the scientist on Cook's first voyage, and had probably met Captain Cook himself, as well, quite possibly, as Omai, the sociable South Sea Islander who had been brought to England by a ship accompanying Cook. Baron Munchausen refers to Omai familiarly as "my old acquaintance" (152). Raspe's interest in Cook's voyages went further, however, than even eyewitness accounts could satisfy, and when the third voyage was announced to explore for the northwest passage from the Pacific side, Raspe applied to go along as geologist. Not surprisingly the confessed embezzler was rejected.27 But in one of the disputed tales the Baron participates in the search that his creator had missed. From his perch on the back of a flying eagle Munchausen watches without luck for the long sought waterway.

Raspe was interested in a wide range of antiquities.28 After he had been in England for several years, he became especially fascinated by the idea of deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphics. The project inspired him to propose a "literary expedition" to Egypt to discover manuscripts in Coptic libraries.29 Both deciphering and discovery were fruitless until transformed and parodied by Baron Munchausen's magical knack for success. In the tales the whole puzzle of remote dialects is subjected to ridicule by means of various quotations and translations from fictitious languages (94, 119, 125). The most elaborate occurs in the sequel; an inscription in a purported Scythian script is reproduced and explicated to demonstrate that a central African tribe which Munchausen visits is descended from people from the moon (119). And Munchausen has equal success in the sequel discovering manuscripts, for while digging the Suez Canal the baron accidentally disinters the entire Alexandrine Library together with some of the original scholars still alive inside (157). Surely these were enjoyable pranks for the disappointed expedition leader.

Raspe alway relished the practical applications of science. He gave his Account of Some German Volcanoes the subtitle An Essay of Physical Geography for Philosophers and Miners. And when he wrote to Captain Cook, he stressed that his scholarly work, which was "planned less for speculation than for useful practical Science," was "established upon facts only,"30 a claim he frequently repeated. The Baron too insists on facts, chiefly of course to emphasize his claim to veracity, but also in playful Imitation of the scientific spirit. "I have ever confined myself to facts" (71), Munchausen declares, and, "Here facts must be held sacred" (40). The table of contents, appearing only in the "Third" Edition (1786), is entitled, "Heads of the established FACTS contained in this volume."

And from then on the text, in accordance with one of Raspe's pedantic tendencies, has footnotes.

Raspe's loosely structured book centers on a figure who is a lighthearted wish-fulfillment for the author. The baron reveals a number of traces of Raspe's personality and predicaments, as well as his interests. Thus Raspe's experience is apparent in such convenient precepts as, "A great mind is never known but in adversity" (105), and his disposition toward science in such enthusiastic exclamations as, "What an acquisition to Philosophy!" (110).

Nevertheless, aside from the rather obscure antiquarian interests that Raspe and his fictional baron shared, these correspondences are too general to single out Raspe from other well-informed hacks whom the original publisher Kearsley might have hired. The most striking indications that the German exile wrote the entire Munchausen are, first, the coincidence of political views at certain dates, and, second, some quite specific allusions to particular geological issues that Raspe had written about and to the type of field work he had done.

Raspe's innovative spirit did not extend to his political views. Despite his bad experiences with "that cruel German Court, which has sacrificed me,"31 he was not tempted by democratic experiments. In all the letters he wrote to Benjamin Franklin during the American Revolution he only once referred to the war and then with the ambiguous wish that good might come from evil.32 Raspe was a monarchist. At the very time when George III was widely reviled and even suspected of trying to restore despotism, Raspe had written loyally, in the third letter reprinted by Bahrdt, that the British king, who was his natural prince, had his good qualities.33 He concluded the undisputed first edition with an obvious departure from the real Baron Munchausen's stories, quoting, "God bless great George our King" (24).

Years later, when the French Revolution erupted, Raspe was incensed. On November 2, 1792, in one of his last preserved private letters, he wrote to his employer, the powerful industrialist Matthew Boulton, about the awful behavior of the French public. He imagines how the first ideal of the Revolution, liberty, might be accurately depicted: "To do full justice to that Liberty, she should be like a St. Giles's Sans-Petticoat Bunter, intoxicated with strong beer and gin and grinning at an Aristocrat's head, just chopped off by the guillotine in the Background."34 The Munchausen sequel is dated November l, 1792, the day before Raspe's letter to Boulton. It concludes on the same note of fury with the rabble. The Baron discovers the French National Assembly in a Company of fishwives conducting a pagan ceremony. When, much shocked by the scene, Munchausen charges into the crowd with drawn sword, "their cries were horrible, like the shrieks of witches and enchanters versed in magic and the black art" (164). In consideration of his English readers, Raspe refrained here from repeating the same insulting image of the St. Giles apprentice, but in his last gallant act, Munchausen appears at just the right moment to save Marie Antoinette and the King from the mob. With thoughts of them the sequel, and thereby the classic text, closes. Again the Baron's actions parallel Raspe's sympathies. That this is not merely a coincidence is underscored by the November dates.35

In geological matters the disputed editions of the tales are a veritable catalogue of the issues most interesting to Raspe. The Baron discovers great mountains of marble (184) and mountains in the sea (51); he refers to earthquakes (114), suggests the origin of the Baltic Sea (132), and encounters a floating island (144), all topics Raspe had dealt with in his geological publications.36 When he wrote to Captain Cook about the research he would like to conduct on the third voyage, the hopeful geologist declared positively that the sand of the volcanic islands in the Pacific would be mixed with gold dust "and perhaps with some Diamonds and finer stones."37 In the Munchausen sequel a similar remark is made about Africa, when one of the characters astutely exclaims:" What prodigious wealth of gold and diamonds must not lie concealed in those torrid regions when the very rivers on the coast pour forth continual specimens of golden sands" (96). The Statement reveals a mind that can judge what is implied about the interior of Africa when alluvial gold is found on its shores. The baron, in fact, does find gold. He does not find the diamonds that Raspe had predicted to Cook and which Raspe felt were overrated anyway, but he discovers something else instead: "All appeared an extreme fine sand, mixed with gold-dust and little sparkling pearls" (115).

Raspe's most significant geological work and his primary interest concerned volcanic phenomena. Again the baron investigates volcanoes. He explores the inner workings of Mount Etna, ascertaining that the mountain was one of Vulcan's workshops linked to Mount Vesuvius by "a passage three hundred and fifty leagues under the bed of the sea" (66-67).

Raspe had never been to Italy, so it is not surprising that the most striking geological remark of all concerns not the baron's exploits along the Mediterranean but in England. It happens in a seemingly casual but deliberate description of a previously unidentified volcanic crater. While he was still in Germany Raspe had begun doing fieldwork to locate the weathered and eroded remnants of ancient volcanic eruptions. Now he slipped into his Munchausen tales a provocative remark about a formation near London. The Baron's visit to Etna gives him the opportunity. Since, as he says, Mount Etna's eruptions have "been so frequently noticed by different travellers," the baron promises not to "tire you with descriptions of objects you are already acquainted with." Instead he compares Etna with a formation he has found in England. Raspe has Munchausen observe that when he walked around Etna's crater it "appeared to be fifty times at least as capacious as the Devil's Punch-Bowl near Peterfield, on the Portsmouth Road, but not so broad at the bottom ..." (65). This is the work of an irrepressible scientist who had not seen Etna but had definitely walked around the Devil's Punch-Bowl and easily concluded what it really was. Such conclusions were controversial at the time, when geologists still had a vastly oversimplified view of the age and development of the earth. By allowing the exact identification, "Devil's Punch-Bowl near Peterfield, on the Portsmouth Road/' to intrude into the fanciful tale, the serious fieldworker Raspe announces himself.

Arguing that the continuations are by a single author does not mean neglecting the changes that occur in Munchausen's character from the first edition to the last, over six years later. Much as Raspe's own name had been so fearfully marred before, the baron's reputation suffered an unexpected reversal too during the course of the enlarged editions. Very rapidly the view of him as a charming narrator recounting his tales for the entertainment and edification of his audience changed into the image of a fast-talking buffoon. He came to be regarded as a liar and clown, a man who committed ridiculous acts and made outrageous claims. His audience began laughing at him as a ludicrous figure, instead of with him as a man of wit.

The decay in his position from sovereign story-teller to rascal was reflected in the illustrations of the tales. The original plates, which were probably Raspe's work or based on his sketches,38 show the baron as a correctly dressed, usually neatly wigged, very young man. Once he became indistinguishable from the liars whom he was intended to satirize, this appearance completely changed. The transformation first occurs in the frontispiece to the sequel, where he glowers in a quarter length portrait as a scarred and cynical middle-aged adventurer. Since some of the other new plates in the sequel continue to show the neat young man, Munchausen's degeneration was still not complete. But as soon as the outlandish tales came to be regarded as lies rather than as the unmasking of lies, the baron inevitably turned into a scoundrel.

Originally, Raspe had not wished to humiliate his baron or treat him with scorn. In fact, he respected his aristocratic protagonist and did not consider him a liar.3? The baron, the "Advertisement to the Second Edition" explained, "is himself a man of great honor and takes delight in exposing those who are addicted to deceptions of every kind, which he does with great pleasantry by relating the stories in large companies now presented to the public in this little collection . . ." (1). The note was repeated in practically all the following editions. Hawkins had reported similarly that Raspe had often told him "these stories were related by a real Baron Munchhausen. . .to ridicule the disposition for the Marvelous which he observed in some of his acquaintances." The protagonist of the stories is famous and admired, accepted at court, and supported in all his schemes. He is, in many ways, everything that Raspe had hoped to become.

Another figure, the Marquis de Bellecourt, who appears in the sequel, more closely reflects Raspe's actual unfortunate fate. For an undisclosed cause the Marquis has fallen into disgrace. His effort to respond to the disaster is described in vivid detail. "Yes, I am confident," he says, "that I have acted according to the strictest sentiments of justice and of loyalty to my sovereign." He resolves to defend himself:

"Conscious of my own integrity, I will try again—I will go boldly up." The Marquis de Bellecourt saw the opportunity; he advanced three paces, put his hand upon his breast and bowed. "Permit me," said he, "with the most profound respect, to—" His tongue faltered—he could scarcely believe his sight, for at that moment the whole Company were moving out of the room. He found himself almost alone, deserted by every one. "What!" said he, "and did he turn upon his heel with the most marked contempt? Would he not speak to me? Would he not ever hear me utter a word in my defence?" His heart died within him—not even a look, a smile from any one. "My friends! Do they not know me? Do they not see me? Alas! they fear to catch the contagion of my—Then," said he, "adieu!—'tis more than I can bear. I shall go to my country seat, and never, never will return. Adieu, fond court, adieu!—" (97)

While the story of the marquis may be topical and certainly has its literary precedents—Carswell points out the similarity of language to some of the scurrilous scenes in Sterne—the predicament as a disgraced courtier is still the key point. In one of his letters from England Raspe had traced the line of such sufferers from Francis Bacon to himself. While the baron is a wish fulfillment, the Marquis is a more accurate self-portrait.

The argument favoring Raspe's authorship of the English Munchausen Tales is chiefly that allusions throughout all the continuations, from the first edition to the sequel, match Rudolf Erich Raspe's thoughts and interests during the same years. If the changes of style apparent in the continuations can be accounted for by Raspe's versatile skills, well practised through his diverse translations, it is not necessary to assume that the different stories were actually written by different hands. Less Information is available to show whether he wrote the original Vade Mecum stories, but nothing has been found to discourage that supposition.

And yet, if Raspe did write the entire Munchausen collection, it might seem strange that he never publicly acknowledged a work which became an internationl best-seller, with a translation within a year of publication into German, printings in Dublin, Ireland, and Newport, Rhode Island, also in 1786, followed by two more "reprints" the next year in Norfolk, Virginia, and New York, and a French translation in Paris. Confronted with all this success, Raspe did not in fact keep his authorship perfectly secret. People in Cornwall, where he probably wrote the first edition, knew Raspe had written the Munchausen tales because one of them, William Petherick, still spoke of it years later.40 As we have seen, at least one of Raspe's scholarly English friends, John Hawkins, knew as well. In Germany Meusel knew part of the story for he associates Raspe with the tales in his article on Raspe published in 181l.41 The German translator, Bürger, evidently was also informed since it was his friend and biographer who first made Raspe's role widely known. Significantly, none of these witnesses ever suggested that Raspe wrote only part of the tales, and Bürger, for instance, drew on the enlarged editions for his translation.

According to Hawkins, who had been to Germany and met Raspe's old friends there, his crimes of long ago in Cassel were forgotten, for Hawkins wrote to Lyell: "In Germany Raspe was known only as a man of Learning" (55). That would have warmed Raspe's heart. Not that he was not pleased with the precious money his chapbook brought in—and by writing enlargements he was able to earn even more. But he must have been delighted by the sheer success of his literary creation.

Perhaps, however, he was still not sure how to reconcile this lighthearted masterpiece with his scholarly reputation. And he may well have feared that any public association between the scholar's name and these frivolous works might reawaken distressing memories of his earlier follies. Raspe preferred to be free of responsibility for the unusual and irregulär baron, who claimed so vigorously to speak only the truth. Yet he did feel the joy of his anonymous success.42

The disgraced Marquis in the sequel, which was written two years before Raspe's death, had attempted vainly to explain his crime to his prince and the court. His listeners abruptly withdrew, but Munchausen, the successful, wrote an apostrophe of praise to the fallen courtier, promising him ultimate though anonymous vindication. "Peace to thy ghost, most noble marquis! a King of kings shall pity thee; and thousands who are yet unborn shall owe their happiness to thee, and have cause to bless the thousands, perhaps that shall never even know thy name; but Munchausen's seif shall celebrate thy glory!" (97). If Raspe wrote this and intended it to refer not just to the Marquis but to himself as well, as I believe he did, he realized that he had accomplished something that was great in its own way, whether acknowledged before and by his most respected contemporaries or not. Through Munchausen, he knew, his fame was assured, even though his name might be unknown.

———

24 The Real Munchausen: Authentic Tales of the Fabulous Baron of Bodenwerder (New York: Devin-Adair, 1960), p. 80.

25 Carswell, Prospector, p. 115.220 Rudolf Erich Raspe and the Munchausen Tales

26 Ruth P. Dawson, "Georg Forster's Reise um die Welt: A Travelogue in its Eighteenth-Century Context," Diss. University of Michigan, 1973, pp. 38-42.

27 Ruth P. Dawson, "The Geologist Captain Cook Refused," Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, 8 (1979), 267-90.

28 Hallo retraces Raspe's antiquarian activities in Germany and considers him a pioneer in the revival of appreciation of medieval German art, architecture, and literature.

29 Carswell, p. 141.

30 Dawson, "Raspe," p. 279.

31 Robert L. Kahn, "Some Unpublished Raspe-Franklin Letters," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 99 (1955), p. 129.

32 Kahn, p. 132.

33 Literarisches Correspondenz und Intelligenzblatt, 122 (1778), pp. 173—74, and 123 (15 April 1778), pp. 175-80.

34 Cited in Carswell, Prospector, p. 249.

35 Admittedly, it is difficult to know exactly how to Interpret the date on the sequel, because it appears on the imprint on the title page rather than with the Preface or elsewhere. Nevertheless, considering the references with the stories to the most recent events in France, it is likely that November l is very close to the date of writing.

36 For Raspe's interest in marble, see Carswell, Prospector, p. 168, p. 238; see Raspe, Introduction, for floating islands (pp. 46—50), the disappearance of an isthmus (pp. 40—44), submarine mountains and earthquakes (throughout).

37 Dawson, "Raspe," p. 281.

38 Wackermann, p. 18. Wackermann also includes plates which show the change in the baron's appearance, plates v-xi.

39 This interpretation is in contrast to those offered by both Carswell, who suggests that Raspe intentionally used his figure in revenge for old grievances (Prospector, 32; Travels, xxix), and Werner Rudolf Schweizer, who carries this claim even further. Schweizer mentions a disagreement in Hanover between Raspe and the baron's relative, Gerlach von Münchhausen, a high Hanoverian official. He asserts an additional, more general motive: "Raspe hegte ein Rachegefühl gegen die höhere Gesellschaft, die ihn hatte fallen lassen wegen seiner Unterschlagungen." Thus he sees in Raspe's Munchausen figure an intentional insult, calls him a clown, and summons the appropriate Image: "Ein Clown muß seine ernste männliche Würde ablegen, damit er seiner burlesken Rolle gerecht wird, und er tut es, indem er in einer lächerlichen verzerrten Erscheinung, einer bunten, ja lumpigen Tracht auftritt und sich herumdrücken, jagen, verspotten lasst. . ." Münchhausen und Münchhausiaden (Bern: Francke, 1969), p. 56. In fact, Schweizer misapprehends the later public interpretation and the later illustrations as corresponding with Raspe's original intentions. Nor does his Suggestion of a revenge theory bear close scrutiny. By the time of writing, Raspe's malice would be much more likely addressed to the Duke of Hesse, or members of his court, people to whom he had applied for reinstatement into German society (article in preparation). But when the busy writer set out to scribble the tales, even those events lay almost a decade in the past. Furthermore, although his model, whom he explicitly identifies in the Preface to the first edition, indeed suffered from the characterization, Raspe meant him no harm with it. As for Gerlach von Münchhausen, he was only a distant relative of the story-telling baron and had died in 1770 anyway. After all Raspe's other struggles and disappointments it is hard to imagine that in the 1780's he was still bitter toward that long dead man. The idea that Raspe "compiled the book in revenge" is traceable to Sir Walter Scott, The Letters of Sir Walter Scott, III (London: Constable, 1932), 198.

40 Gentleman's Magazine, 202 (1857), 2, as quoted in Wackermann, p. 24.

41 Lexikon der von 1750 bis 1800 gestorbenen deutschen Schriftsteller, XI (Leipzig: 1811), 49ff., as quoted in Wackermann, p. 23.

42 For the opposite point of view, see

Carswell, Prospector, p. 191.

In: Lessing Yearbook 16 (1984), S. 205-220.

Der Fortsetzungsband A Sequel setzt sich, wie das Titelblatt ankündigt, mit dem

1790 erschienenen Bericht des schottischen Adeligen James Bruce über dessen

Afrikaexpedition in den Jahren 1768 bis 1773 auseinander, geht aber deutlich

darüber hinaus. Hier gibt es eine durchgehende Handlung und die Kapitel sind

inhaltlich verbunden; die Beschreibungen sind üppiger, fantastischer – und die

Satire ist unverblümt, mit durchgängigen Bezügen zur englischen und zur globalen

Tagespolitik der 1780er-Jahre. So verwickelt sich der Baron mit seinem

fantastischen Gefolge in den Sklavenhandel, versucht, einem afrikanischen Volk

britische Sitten beizubringen, baut Kanäle und Luftschiffe, macht in Amerika und

Indien imperiale Eroberungen mit und gerät abschließend in die Französische

Revolution. Zugleich liefert der Band Persiflagen auf bekannte Literaturstile,

etwa auf die Empfindsamkeit bei Oliver Goldsmith und Laurence Sterne und auf

Cervantes' Don Quijote.

Howald/Wiebel 2015b, S. 216f.

Kommen wir auf die Frage zurück, wie weit Raspes Autorschaft reicht. Die Sequel (= Fortsetzung) als ganz neues Buch nimmt eine Sonderstellung ein. Das Titelblatt enthält eine Widmung an den Nilquellenforscher James Bruce, dessen Bericht über das Innere Afrikas bei den Lesern heftigen Unglauben ausgelöst hat. Die Widmung verleitet, die Sequel lediglich als Satire auf den Inhalt von Bruce's Reisebeschreibung zu verstehen. A Sequel entpuppt sich jedoch als ein Feuerwerk von Anspielungen auf die europäische Politik und Kultur, Bruce spielt gar keine Rolle. Der Baron kämpft gegen Don Quixote, trifft Louis XVI. mit Marie Antoinette, siegt glorreich in Indien und beherrscht in Afrika ein Volk Einheimischer durch die Verteilung von Leckereien, die zugleich Lug und Betrug sind (= fudge). A Sequel ist durchsetzt mit witzigen Anspielungen auf die Französische Revolution.

Die englischen Verleger verkaufen Munchausen seit etwa 1810 mit beiden Teilen –

seit 1859 mit Raspe auf dem Titel. Die amerikanische Literaturwissenschaftlerin

Ruth P. Dawson hat als bisher einzige mit Sorgfalt die Sequel untersucht und

Indizien für Raspes Autorschaft erarbeitet, allerdings keinen Beweis.

Anspruchsniveau und Anspielungsreichtum sprechen jedoch auf jeden Fall gegen die

verbreitete Ansicht, Viel- und Billigschreiber des Verlages seien die Urheber.

Von den neuen kleinen Indizien, die für Raspe sprechen, sei nur ein Beispiel

genannt: In der Sequel gelingt es Munchausen, das Wrack der berühmten, 1782

gesunkenen „Royal George“ zu heben. Mit der indirekten Erwähnung dieses Schiffs

beginnen auch die Seeabenteuer in der zweiten Ausgabe des Munchausen von April

1786, für die Raspe als Autor unangefochten ist: „l embarked at Portsmouth in a

first-rate English man of war, of one hundred guns.“ Der first-rate English man

of war bezeichnet ein außerordentlich großes Schlachtschiff, und die 100 Kanonen

verweisen auf das Genannte: Dieses später so berühmte Schiff hatte Raspe 1779 im

Hafen von Portsmouth im Bau gesehen, „den St. George von hundert Kanonen, oder

vielmehr sein Gerippe“. Diese Beobachtung ist notiert in dem 1784 publizierten

Teil des Journals, das Raspe als Leiter einer Reisegruppe um den kurländischen

Baron Offenberg führte. Hierin finden sich noch weitere Bezüge zu den

Munchausen-Editionen und damit Belege für Raspes Autorschaft.

Bernhard Wiebel: Raspes Münchhausen lügt nicht - oder: Munchausen on German

Volcano. In: Linnebach 2005, S. 121f.

Politische Zensur war schon immer ein geeignetes Werbemittel. George Kearsley

schrieb 1787 in einem Verlagskatalog: »Die Abenteuer des Barons in Gibraltar

sind verboten in der französischen und holländischen Ausgabe, aber vollständig

gedruckt in der englischen.« Tatsächlich fehlt in der französischen ersten

Ausgabe die Passage, in der die Franzosen unter dem Grafen von Artois von den

Engländern von Gibraltar bis nach Paris in die Flucht geschlagen werden. In der

holländischen ersten Ausgabe wird die ganze Passage mit anderen Akteuren

umgeschrieben. Beide Ausgaben verharmlosen auch die Szene, in der Papst Clemens

XIV. eine Nacht bei einer Austernverkäuferin verbringt. Tatsächlich sind beide

Bände durchsetzt von Anspielungen auf historische und politische Ereignisse.

Howald/Wiebel 2015b, S. 224f.

Rudolf Erich Raspe war vielfach engagiert, Zeitgenosse war er in seiner unermüdlichen aufklärerischen Neugier. Insbesondere als sowohl empirischer wie theoretischer Naturforscher trug er zu der sich entwickelnden Geologie als einer Leitwissenschaft bei, die auch geschichtsphilosophische Haltungen prägte. Die Vulkanthematik ist etwa in Kapitel XX verarbeitet: Münchhausen lässt sich vom göttlichen Schmied Vulkan das Funktionieren des Ätnas erklären. Auch die Untersuchungen zu Rohstoffvorkommen, die Raspe in zahlreichen fachlichen Publikationen erörterte, finden ihren literarischen Niederschlag im Sequel, zum Beispiel in der Episode über die Expedition des Barons durch Afrika (Kapitel l und V). Ebenso aufmerksam verfolgte Raspe technische Entwicklungen. In den »Seeabenteuern« geht es jenseits des Seemannsgarns oft auch um die Erforschung einer säkularisierten Welt und beiläufig um den Umgang mit der Natur, der in der Dialektik der Aufklärung zuweilen in Gewalt gegen die tierischen und menschlichen Bewohner bislang uneroberter Landschaften umschlägt. Eine besondere Rolle nimmt die Luftschifffahrt als damalige Herausforderung an die technischen Fähigkeiten und die weltanschaulichen Positionen ein. Münchhausen bedient sich neuartiger Ballone, künstlicher Schwingen und von ihm gesteuerter Adler, um sich des Luftraums zu bemächtigen. Auch der Kanalbau beschäftigte ihn offensichtlich. In Kapitel III des Sequel gibt sich der Baron als Urheber eines rudimentären Sueskanals zu erkennen; in Kapital XII organisiert er dann den Bau des Panamakanals, um schließlich in Kapitel XIII den Durchstich des Sueskanals als Mittel zur Völkerverständigung anzuleiten. Selbst die wiederholte wundersame Entdeckung oder Herstellung exotischer Nahrungsmittel ist nicht nur eine Anspielung auf das Motiv des Schlaraffenlands und eine Ironisierung englischer kulinarischer Vorlieben für Rosinenpudding und Beefsteaks. Sie ist auch ein Ausdruck der zeitgenössischen Suche nach Fortschritten in der Landwirtschaft, um die rasch wachsende Bevölkerung Europas zu ernähren. So produziert Münchhausen in Kapitel IV einen besonders ertragreichen Dünger - eine Aufgabe, die noch bis weit ins 19. Jahrhundert die experimentelle Chemie antrieb.

Ein weiteres Interesse des Altertumswissenschaftlers Raspe taucht mehrfach auf,

nämlich die Frage nach der Verwandtschaft der menschlichen Sprachen, dies

insbesondere im Sequel. Dort behauptet Münchhausen in Kapitel l nicht bloß, dass

er 999 Sprachen spricht, sondern liefert in Kapitel VI auch eine Ableitung der

Sprachen eines afrikanischen Volks, der sagenumwobenen Skythen und der nicht

weniger sagenumwobenen Mondbewohner, von denen ja schon in den »Seeabenteuern«

die Rede war. Die Brücke zwischen Afrika und Großbritannien schmückt dann eine

Inschrift, die als eine Art Esperanto angeboten wird (Kapitel VIII). Ja,

Münchhausen ist keineswegs immer der schneidige, waffengewandte Abenteurer,

sondern eben auch ein Mann der Wissenschaften. Nicht zufällig entdeckt er in

Kapitel XIII die verschollene Bibliothek von Alexandria, belehrt antike

Philosophen über Isaac Newtons Erkenntnisse zur Schwerkraft und befördert die

obskuren Geheimlehren der Alten in der Figur des Hermes Trismegistos ins Museum.

Howald/Wiebel 2015b, S. 225f.

Ein Motiv, das sich bei Raspe durch Leben und Werk zieht, ist die Kritik an der Macht der Kirche. Hessen-Kassel war zu seiner Wirkungszeit ein Brennpunkt religiöser Spannungen. 1749 war der Kronprinz, der spätere Landgraf Friedrich II., heimlich zum Katholizismus übergetreten. Sein Vater, Landgraf Wilhelm VIII., zwang ihn deshalb 1754 in der sogenannten Assekurationsakte, bei seinem Regierungsantritt die protestantische Ausrichtung von Hessen-Kassel zu garantieren und den katholischen Glauben nicht öffentlich auszuüben. An diesen Vertrag hielt sich Friedrich II. nach 1760. Spannungen zwischen den Konfessionen waren allerdings angesichts katholischer Einmischungsversuche nicht ganz zu vermeiden; auf der anderen Seite trug gerade Friedrich durch informelle Kontakte zu katholischen Aufklärern zu einem »aufklärerischen Überkonfessionalismus« bei. Raspe seinerseits hatte vermutlich die Rolle des neutralen Vermittlers, auch im Auftrag des Landgrafen. Als er im Sommer 1773 monatelang in westfälischen Klöstern mittelalterliche Urkunden studierte, verband sich dies mit einer heiklen Mission: Der Landgraf wünschte Informationen über die Jesuitenkollegien in Paderborn und Buren, die ihn in ihrer Notlage nach der Aufhebung ihres Ordens durch Papst Clemens XIV. um Hilfe gebeten hatten. Dass Raspe im Münchhausen diesen Papst, allerdings höchst satirisch, auftreten lässt, könnte ein Widerhall dieser Unternehmungen sein.

Raspe hatte sich schon in Anmerkungen zu dem 1778 von ihm aus dem Englischen ins

Deutsche übersetzten Gentoo-Kodex über hinduistische Gesetze entschieden

antikirchlich geäußert. Da mochte es ihm entgegenkommen, dass bereits die

M-h-s-nschen Geschichten im Vade Mecum einen religionskritischen Akzent

angeschlagen hatten: so etwa die der Geschichte des Heiligen Martin

nachempfundene Erzählung, wie der Baron einem Armen seinen Mantel gibt, worauf

Gott höchstpersönlich eine Belohnung verspricht und nicht eben statuskonform den

Teufel als Zeugen anruft. Auch der Schuss auf die Kirchturmspitze, um das dort

angebundene Pferd zu befreien, verrät nicht gerade viel Respekt gegenüber

kirchlichen Symbolen. Raspe übernahm beide Episoden in Kapitel II und baute die

plane Anekdote über den mit Kirschkernen beschossenen Hirsch zu einer

mythenkritischen Geschichte über den heiligen Hubertus aus, die er damit

beschließt, dass die Kirchenmänner für das Aufpflanzen von Hörnern bekannt seien

(Kapitel IV). Auch die Nacherzählung über den biblischen König David, dessen

Geliebte Bathseba und den Ehestreit um die königliche Stein-Schleuder in Kapitel

XII ist höchst frivol gehalten. Einen Höhepunkt findet diese Haltung in der

scharfen, geradezu ehrenrührigen Episode mit dem erotomanen Papst Clemens XIV. –

in schöner Symmetrie in Kapitel XIV.

Howald/Wiebel 2015b, S. 226f.

Schnell und zielgerichtet reagierte Raspe auf zeitgenössische Ereignisse. Das

zeigt sich etwa daran, wie er die englische Expansion in Indien oder die

Französische Revolution ins Sequel einarbeitet. Raspe selbst hatte sich zuerst

für die Französische Revolution ausgesprochen, äußerte 1792 jedoch Kritik an

deren Umschlag in den »terreur«. Wenn sich der Baron aber als konservativer

Monarchist entpuppt, so wird das nicht nur im »Vorwort« relativiert, sondern

auch im Schlusssatz: Münchhausen weist jede Verantwortung für die politische

Unzulänglichkeit des Feudalsystems von sich, da der von ihm befreite König aus

eigener Schuld wieder gefangen genommen worden sei, weil er zu lange zu Tisch

gesessen habe.

Howald/Wiebel 2015b, S. 232f.

|

PREFACE.

Baron Munchausen has certainly been productive of much benefit to the literary world: The numbers of egregious travellers have been such, that they demanded a very Gulliver to surpass them. If Baron de Tott dauntlessly discharged an enormous piece of artillery, the Baron Munchausen has done more; he has taken it and swam with it across the sea. When travellers are solicitous to be the heroes of their own story, surely they must admit to superiority, and blush at seeing themselves out-done by the renowned Munchausen: I doubt whether any one hitherto, Pantagruel, Gargantua, Captain Lemuel, or de Tott, has been able to out-do our Baron in this species of excellence: And as at present our curiosity seems much directed to the interior of Africa, it must be edifying to have the real relation of Munchausen's adventures there before any further intelligence arrives; for he seems to adapt himself and his exploits to the spirit of the times, and recounts what he thinks should be most interesting to his auditors. I do not say that the Baron, in the following stories, means a satire on any political matters whatever. No; but if the reader understands them so, I cannot help it. If the Baron meets with a parcel of negro ships carrying whites into slavery to work upon their plantations in a cold climate, should we therefore imagine that he intends a reflection on the present traffic in human flesh? And that, if the negroes should do so, it would be simple justice, as retaliation is the law of God! If we were to think this a reflection on any present commercial or political matter, we should be tempted to imagine, perhaps, some political ideas conveyed in every page, in every sentence of the whole. Whether such things are or are not the intentions of the Baron the reader must judge. We have had not only wonderful travellers in this vile world, but splenetic travellers, and of these not a few, and also conspicuous enough. It is a pity, therefore, that the Baron has not endeavoured to surpass them also in this species of story-telling. Who is it can read the travels of Smellfungus, as Sterne calls him, without admiration? To think that a person from the North of Scotland should travel through some of the finest countries in Europe, and find fault with everything he meets—nothing to please him! And therefore, methinks, the Tour to the Hebrides is more excusable, and also perhaps Mr. Twiss's Tour in Ireland. Dr. Johnson, bred in the luxuriance of London, with more reason should become cross and splenetic in the bleak and dreary regions of the Hebrides. The Baron, in the following work, seems to be sometimes philosophical; his account of the language of the interior of Africa, and its analogy with that of the inhabitants of the moon, show him to be profoundly versed in the etymological antiquities of nations, and throw new light upon the abstruse history of the ancient Scythians, and the Collectanea. His endeavour to abolish the custom of eating live flesh in the interior of Africa, as described in Bruce's Travels, is truly humane. But far be it from me to suppose, that by Gog and Magog and the Lord Mayor's show he means a satire upon any person or body of persons whatever: or, by a tedious litigated trial of blind judges and dumb matrons following a wild goose chase all round the world, he should glance at any trial whatever. Nevertheless, I must allow that it was extremely presumptuous in Munchausen to tell half the sovereigns of the world that they were wrong, and advise them what they ought to do; and that instead of ordering millions of their subjects to massacre one another, it would be more to their interest to employ their forces in concert for the general good; as if he knew better than the Empress of Russia, the Grand Vizier, Prince Potemkin, or any other butcher in the world. But that he should be a royal Aristocrat, and take the part of the injured Queen of France in the present political drama, I am not at all surprised; but I suppose his mind was fired by reading the pamphlet written by Mr. Burke. |

Baron de Tott:

François Baron de Tott (1733-1793) war französischer Offizier ungarischer

Herkunft. 1755 reiste er als Sekretär seines Onkels Charles Gravier, Comte

de Vergennes nach Konstantinopel, wo dieser als französischer Botschafter

wirkte. Er lernte Türkisch und sammelte Informationen über das Khanat auf

der Krim. 1763 kehrte er nach Paris zurück und wurde 1766 von der

französischen Regierung in die Schweiz geschickt. 1767 wurde er zum Konsul

auf der Krim ernannt, wo er die Krimtataren zum Aufstand gegen das

kaiserliche Russland ermutigte. François de Tott spielte während des

russisch-türkischen Krieges (1768–1774) eine wichtige Rolle als Beauftragter

der osmanischen Regierung. Er reformierte das osmanische Militär und

organisierte mobile Artillerie-Verbände. Nach dem Russisch-Türkischen Krieg

1770–1774 mussten die Osmanen im Frieden von Küçük Kaynarca 1774 die

Unabhängigkeit der Krim anerkennen. 1783 kam die Krim durch Annexion unter

mittelbare russische Herrschaft: Anschließend bereiste er das Osmanische

Reich und besuchte Küstenstädte rund um das Mittelmeer, darunter Alexandria,

Aleppo, Smyrna, Saloniki und Tunis. Seine Memoiren wurden in viele Sprachen

übersetzt.

François Baron de Tott (1733-1793) Pantagruel,

Gargantua:

Gargantua und Pantagruel (engl. The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel)

ist ein Romanzyklus von François Rabelais, dessen fünf Bände 1532,

1534, 1545, 1552 und 1564 erschienen; vor allem die ersten beiden Bände

waren sehr erfolgreich. Der zuerst verfasste Pantagruel, für den

Rabelais zunächst keine Fortsetzung geplant hatte, trägt den Titel Les

horribles et épouvantables faits et prouesses du très renommé Pantagruel,

Roi des Dipsodes, fils du grand géant Gargantua. Composés nouvellement par

maître Alcofrybas Nasier (deutsch „Die schrecklichen und entsetzlichen

Abenteuer und Heldentaten des hochberühmten Pantagruel, König der Dipsoden,

Sohn des großen Riesen Gargantua. Neu zusammengestellt von Meister

Alcofrybas Nasier“ – ein Anagramm aus Francoys Rabelais). Das Werk war also

sogleich als unter einem witzigen Pseudonym veröffentlichte Parodie der

Gattung Ritterroman und damit als humoristisch erkennbar.

Frontispiece for volume I of Francois Rabelais's The Works of Francis Rabelais, M.D. London 1737. The works of Francis Rabelais, M.D. London: MDCCXXXVII [1737].

Captain Lemuel:

Ich-Erzähler in Gullivers Reisen (englisch Gulliver’s Travels),

einem satirischen Roman des irischen Schriftstellers, anglikanischen

Priesters und Politikers Jonathan Swift (1667-1745). In der Originalfassung

besteht der Roman aus vier Teilen und wurde 1726 unter dem Titel “Travels

into Several Remote Nations of the World” veröffentlicht. In anschaulicher

Erzählweise bringt Swift seine Verbitterung über zeitgenössische Missstände

und seine Auffassung von der Relativität der menschlichen Werte zum

Ausdruck. Durch die anschauliche Erzählweise der zweiteiligen

Kinderbuchausgabe, in welcher Gulliver erst das Land der Zwerge entdeckt und

dann im Land der Riesen landet, und in der die sozialkritischen und

satirischen Positionen fehlen, wurde das Werk zu einem weltbekannten

Jugendbuch. Der Roman ist, nach Campanellas Civitas solis und Bacons Nova

Atlantis, der Höhepunkt einer im Gegensatz zu religiösen Entwürfen stehenden

Gattung, die ohne unmittelbare Wirklichkeitsansprüche Bilder einer idealen

Gesellschaft zum Thema hat.

Travels into several Remote Nations of the World. In Four parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships. VOL. I. [By Jonathan Swift.] London. MDCCXXVI.

Vergl. den Kommentar zu Bürger 1788, Zehntes See-Abenteuer. |

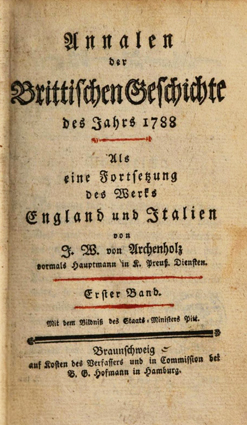

our curiosity seems much directed to

the interior of Africa: Im Juni 1788 war

in London von führenden Intellektuellen und Unternehmern die Association for

Promotimg the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa gegründet worden, die

verschiedene Expeditionen finanzierte. Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz,

Herausgeber der Annalen der britischen Geschichte, druckte schon im

ersten Band dieser Reihe, der das Jahr 1788 betraf, große Passagen des Statuts

dieser Gesellschaft in deutscher Übersetzung ab (Annalen, erster Band,

Wien1789, S. 209-211). Raspe war mit Archenholz gut bekannt und wird dieses

Statut wohl gekannt haben.

Howald/Wiebel 2015, S. 112.

Die African Association (The Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa) war eine der so genannten Afrikanischen Gesellschaften. Sie wurde am 9. Juni 1788 in London von zwölf einflussreichen Männern gegründet. 1831 ging aus der African Association die Royal Geographical Society hervor. Die Mitgliederzahl stieg bis 1790 auf 95 an. Darunter waren auch etliche Gegner der Sklaverei: neben dem Vorstand Beaufoy auch der Parlamentarier William Wilberforce, welcher der Association 1789 beitrat. Auch William Pitt, der Premierminister von Großbritannien, war Mitglied der Gesellschaft.

any further intelligence:

1790 erschien der Bericht des schottischen Reisenden James Bruce

(1730-1794): Travels to Discover the Sources of the Nile in 5 Bänden in

Edinburg, auf den sich Raspe in seiner Widmung bezieht.

Howald/Wiebel 2015, S. 112.

spirit of the times: 1776/77 erschienen bei Kearsley die von Raspe herausgegebenen Briefe Ferbers und Borns (Born 1777). In seinem Vorwort präsentierte sich Raspe als glühender Verehrer der Aufklärung und des „Fortschritts“. Raspe kritisierte, dass viele Menschen aus Eigennutz Erfindungen und Neuerungen nicht weitergeben würden und somit den Fortschritt aufhielten. Hierbei handele es sich oft um die gleichen Personen, die umgekehrt immer schnell bereit seien, eigenen Vorteil aus dem Wissen anderer zu ziehen. So sei es kaum verwunderlich „that progress and improvement has been so slow“. Aber jene Zeit gehe nun dem Ende zu. Raspe schätzte sich glücklich, in einer Ära spürbaren Fortschritts zu leben, und er erkannte die Bedeutung der Aufklärung: „It is only in the wisest and most enlightened ages, that we find some philosophers and wise men, stepping down from the giddy heights of their exalted Station of learning, into which the barbarous igno-rance of the vulgär and their own conceit has placed them, in order to fix, to rectify, and to improve the arts.“ (Born 1777, S. XI.)

Beispiele für einen segensreichen Fortschritt gebe es aus der griechischen und römischen Antike, „and it is in the true spirit of those glorious times, that after so many lost ages of scholastical dullness and mercantile selfishness... many friends of mankind in several parts of Europe have undertaken of late to fix the various arts of mankind for after-times, and establish them upon to the principles of nature and mathematicks, better known at present than any time before.“

Der begnadete Wissenschaftler Raspe war immer auch Praktiker gewesen. Durch sein

gesamtes Leben hindurch zog sich das Bemühen, die Wissenschaft zum physischen

und kulturellen Wohl der Menschheit weiterzuentwickeln und den technischen

Fortschritt dem Menschen verfügbar zu machen. Nicht nur in dieser Hinsicht war

Raspe ein sehr modern denkender Mensch und ein bewundernswerter,

unerschütterlicher Optimist.

Ulrich Schnakenberg: Raspe und die Anfänge der industriellen Revolution in

Großbritannien. In: Linnebach 2005a, S. 54.

Travels through the Bannat of Temeswar, Transylvania, and Hungary, in the Year 1770. Described in a series of letters to Prof. Ferber, on the mines and mountains Of these different Countries. By Baron Ignigo Born, Counsellor of the ROYAL MINES, in Bohemia. To which is added, John James Ferber’s mineralogical history of Bohemia. TRANSLATED from the GERMAN. With some explanatory Notes, and a Preface on the Mechanical Arts, the Art of Mining, and its present State and future Improvement, By R. E. RASPE. LONDON: MDCCLXXVII.

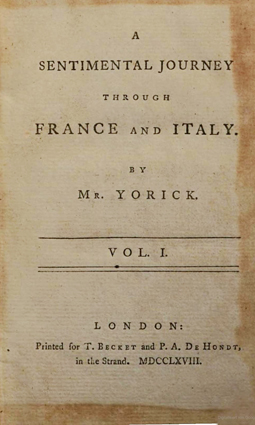

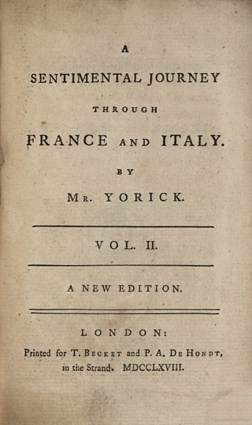

Smellfungus: Geruchspilz. Figur in Laurence Sterne’s Roman A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy aus dem Jahr 1768. Es handelt sich um eine Persiflage auf Tobias Smollett, den Autor von Travels through France and Italy von 1766. Sterne hatte Smollett auf seinen eigenen Reisen in Europa kennengelernt und sich entschieden gegen dessen „spleen, acerbity and quarrelsomeness“ ausgesprochen, weil er die Institutionen und Bräuche der Länder, die er besuchte mit Beschimpfungen überhäuft habe.

Der Begriff „Geruchspilz“ bezeichnet im Englischen eine Person, die sich über bedeutungslose Angelegenheiten beschwert und mit allen streitet, sich niemals positiv in eine Situationen findet und versucht, gegenseitiges Elend unter die Menschen in ihrer Umgebung zu bringen.

Sterne: Laurence Sterne (1713-1768) war ein englisch-irischer Schriftsteller in der Zeit der Aufklärung und Vicar (Pfarrer) der Anglikanischen Kirche. Sein Hauptwerk ist der Roman The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (Leben und Ansichten von Tristram Shandy, Gentleman), dessen beide ersten Bände – trotz negativer Kritiken von Samuel Johnson und Horace Walpole – ihn bereits sehr populär machten. Die weiteren sieben Bände erschienen zwischen 1761 und 1767. Die Neuheit und Eigentümlichkeit seines Stils erregte allgemeines Aufsehen; er wurde der „verzogene Liebling“ der feinen Gesellschaft Londons. Die erste deutsche Ausgabe des Tristram Shandy erschien in der Übersetzung und im Verlag von Johann Joachim Christoph Bode bereits 1774 in Hamburg und markiert den Beginn der Rezeption durch die maßgeblichen deutschsprachigen Autoren der Zeit; so gehörte unter anderen Johann Wolfgang von Goethe zu den Subskribenten dieser Ausgabe.

1767 begann Sterne den Roman A Sentimental Journey Through

France and Italy, erlitt jedoch während der Arbeit an diesem Buch einen –

letzten – Zusammenbruch. Der geistvolle, scharf beobachtende, tief empfindende

Reisende, hinter dessen leicht hingeworfenen Liebesabenteuern man kaum einen

Geistlichen vermutet, ist eines der frischesten und unvergänglichsten

Charakterbilder des 18. Jahrhunderts. Während Sentimental Journey in England

überwiegend als witzige Moralkomödie aufgenommen wurde, betonten viele

Übersetzungen die sentimentale Seite des Buchs, was mit dazu führte, dass Sterne

in den folgenden Jahrzehnten als „Hohepriester des Gefühlskultes“ missverstanden

wurde.

Wikipedia

Joshua Reynolds: Laurence Sterne. Öl auf Leinwand, 1760.

a person from the North of Scotland: gemeint ist James Bruce.

Hebrides: Die Hebriden sind eine Inselgruppe, bis zu 50 Kilometer vor der Nordwestküste Schottlands gelegen. Der Archipel teilt sich morphologisch wie politisch in die Äußeren Hebriden (auch bekannt als Western Isles) und die Inneren Hebriden, getrennt durch den Little Minch und den North Minch sowie die Barrapassage.

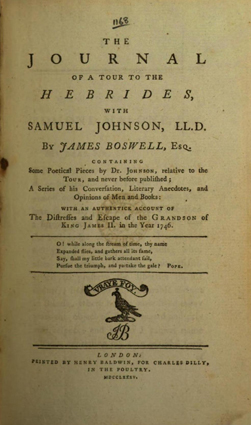

Zwei Reisende haben die Hebriden erforsch und darüber berichtet: Samuel Johnsen und James Boswell.

James Cook erforschte auf seiner zweiten Expedition die Neuen Hebriden, eine Inselgruppe eine rund 700 km lange Inselkette im Südpazifik, 300 km südlich der Salomon-Inseln, 460 km nordöstlich von Neukaledonien und 960 km westlich von Fidschi.

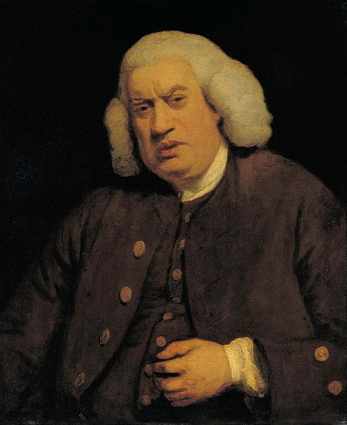

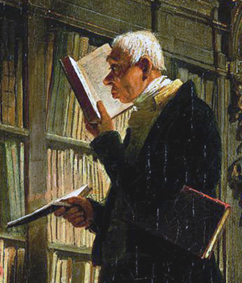

Dr. Johnson: Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) war ein englischer Gelehrter, Lexikograf, Schriftsteller, Dichter und Kritiker.

Die literarische Frucht einer Reise nach Schottland und zu den Hebriden im Jahre

1773 war seine Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland (1775), die ihn

wegen seines darin geäußerten Zweifels an der Echtheit der Dichtungen Ossians in

eine heftige Fehde mit James Macpherson verwickelte. Im Alter von 70 Jahren

schrieb Johnson die Biographien englischer Dichter (The Lives of the Most

Eminent English Poets, 1779–1781) für eine Sammlung der englischen

Klassiker.

Wikipedia

Joshua Reynolds: Doctor Samuel Johnson. Öl auf Leinwand 1772.

James Boswell (1740-1795) war ein schottischer Schriftsteller und Rechtsanwalt. Mit der Biographie seines Freundes Samuel Johnson schuf er eines der bedeutendsten biografischen Werke der englischen Literatur. Daneben ist er als Reiseschriftsteller bekannt: The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, with Samuel Johnson, LL.D. Containing Some Poetical Pieces by Dr. Johnson, relative to the Tour, and never before published; A Series of this Conversation, Literary Anecdotes, and Opinions of Men and Books: with an Authentick Account of the Distresses and Escape of the Grandson of King James II. in the Year 1746. London 1785.

Joshua Reynolds: James Boswell. Öl auf Leinwand 1785.

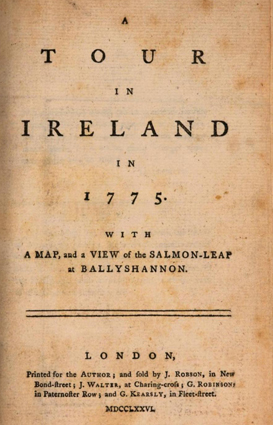

Mr. Twiss's Tour: Richard Twiss (1747–1821) war ein englischer Reiseschriftsteller; die Veröffentlichung von A Tour in Ireland im Jahre 1775 erregte dort Missfallen und führte zu einer Reihe von öffentlichen Entgegnungen.

Richard Twiss, Stich von Mary Dawson Turner, 1814

seems to be sometimes philosophical: Der Baron, den Raspe in seinem Vorwort beschreibt, trägt autobiographische Züge. Nicht nur der Hinweis, er sein „philosophisch“ gestimmt, verweist auf seinen Verfasser; auch die Verweise auf Sprachtheoretische Überlegungen haben mit Raspes eigenen Forschungen zu tun.

1765 gab Rudolf Erich Raspe aus dem Nachlass von Georg Wilhelm Leibnitz die „Oeuvres Philosophiques“ heraus. Dieses Werk wurde in den deutschen Landen begeistert aufgenommen, und sie veränderten schlagartig die ganze bisherige Leibniz-Rezeption, die auf der Grundlage der bislang bekannten Schriften von Leibniz durch den Philosophen und führenden deutschen Aufklärer Christian Wolff (1679-1754) geprägt worden war. Treffend und bewundernd charakterisierte Herder den etwas älteren Freund Raspe später in einem Brief 1774 als den „glücklichen Finder ..., der Leibniz fand.“ Da die kurz danach von Louis Dutens in Genf herausgegebene erste sechsbändige Werkausgabe der Opera omnia (1768) die Nouveaux essais sur l'entendement humain nicht enthielt, mussten alle, die den neuen Leibniz kennen lernen wollten, bis zum Erscheinen der deutschen Übersetzung von J. H. F. Ulrich (1778-80) mit Raspes Edition des französischen Originals arbeiten.

So bekam sie auch um 1766 der Königsberger Privatdozent Immanuel Kant

(1724-1804) in die Hand. Diese Lektüre revolutionierte seinen ganzen bisherigen

rationalen Dogmatismus und eröffnete ihm den Weg zu seiner kritischen

Philosophie, die er 1781 mit der Kritik der reinen Vernunft grundzulegen begann.

Nachdem Kant in den Jahrzehnten davor mit zwar bedeutenden, aber vornehmlich

naturphilosophischen und metaphysischen Schriften hervorgetreten war, legte er

nach der Auseinandersetzung mit Raspes Leibniz-Edition 1770 in seiner

Professoren-Dissertation seine erste erkenntnistheoretische Schrift vor, die

zwar die Wendung zur kritischen Philosophie noch nicht ganz vollzog, wohl aber

bereits in deren Richtung deutete. (De mundi sensibilis atque intelligibilis

forma et principiis) Gleichsam im Versuch, den Streit zwischen den Rationalisten

und Empiristen schlichtend zu unterlaufen, unterscheidet er in dieser Schrift

Von der Form der Sinnen- und Verstandeswelt zunächst scharf die beiden Stämme

unserer Erkenntnis: die Anschauungen (Zeit und Raum) und die Verstandesbegriffe,

um aber gleich darauf die Angewiesenheit beider aufeinander herauszuarbeiten. Es

gibt – so Kant – keine Erfahrungen, die nicht schon durch die Verstandesbegriffe

bestimmt sind, aber es gibt auch keine Verstandeseinsichten, die ohne Bezug auf

die Anschauungen zu Welterkenntnissen führen könnten – ganz wie dies Leibniz

schon gegen Locke herausgestellt hatte. So zeichnet sich für Kant hier die

Aufgabe ab, die er in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft noch entschiedener

verfolgt, nicht Anschauungen und Verstandesbegriffe gegeneinander auszuspielen,

sondern deren Synthesis sowohl in den empirischen Wissenschaften als auch in der

Metaphysik letzter philosophischer Erkenntnisse herauszuarbeiten.

Wolfdietrich Schmied-Kowarzik: Ein Fund von weltgeschichtlicher Bedeutung.

Raspes – Edition von Leibnizʼ Nouveaux Essais. In: Linnebach 2005a, S. 56f.

ancient Scythians: Iranische Reiternomaden, die eine indogermanische Sprache besaßen.

Collectanea: Raspe meint die Beiträge, die in den PROCEEDINGS OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR PROMOTING THE DISCOVERY OF THE INTERIOR PARTS OF AFRICA (LONDON: 1790) der Association for Promotimg the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa vereinsintern veröffentlicht wurden.

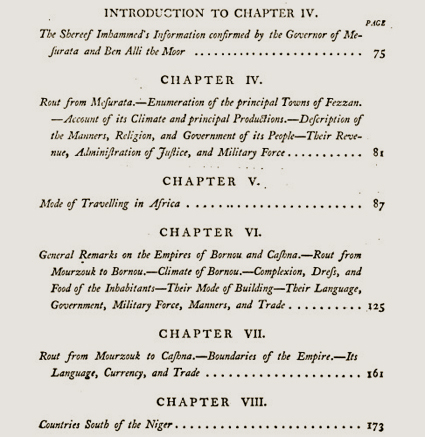

as described in Bruce's Travels:

Die von James Bruce mitgeteilte Nachricht, dass die von ihm besuchten

Völker Fleisch von lebendigem Vieh äßen, erregte in England großes Aufsehen und

wurden nicht geglaubt: siehe Samuel Shaw, An Interesting Narratíve of the

Travels of James Bruce, Esq, into Abyssinia to discover the Source of the Nile.

Howald/Wiebel 2015, S. 115.

Gog and Magog: Die beiden Riesen Gog and Magog sind Wächter der City of London und werden als Figuren bei der jährlichen „Mayor’s Show“, einem Umzug, getragen. Sie stehen als Steinskulpturen am Ausgang der Guild Hall, dem Verwaltungssitz der City of London.

the Lord Mayor's show:

eine der bekanntesten jährlichen Veranstaltungen in

London und eine der ältesten, die bis ins 13. Jahrhundert zurückreicht. Jedes

Jahr wird ein neuer Lord Mayor ernannt, und die öffentliche Parade, die als

seine oder ihre Amtseinführungszeremonie stattfindet, demonstriert,

dass dies einst eines der prominentesten Ämter in England war.

Im Mittelpunkt der Lord Mayor's Show steht eine

Straßenparade, die in ihrer modernen Form eine unbeschwerte Kombination aus

traditionellem britischem Prunk und Elementen des Karnevals ist. Am Tag nach

seiner Vereidigung nehmen der Oberbürgermeister und mehrere andere an einer

Prozession von Guildhall über Mansion House und St. Paul's Cathedral im Herzen

der City of London zu den Royal Courts of Justice am Rande der City of

Westminster teil, wo der

neue Lord Mayor der Krone die Treue schwört. Das Amt

des Lord Mayor stammt aus dem Jahr 1189, bei seiner Einführung wurde

festlegte, dass der Bürgermeister in die königliche Enklave in Westminster

reiste, um sich den Vertretern des Monarchen und den

hochrangigen Richtern als Barons of the Exchequer vorzustellen und

zu Beginn seiner Amtszeit einen

Loyalitäts-Eid gegenüber dem Souverän abzulegen.

Wikipedia

Guildhall 1788

Empress of Russia: Katharina II., genannt Katharina die Große (1729-1796), ab dem 9. Juli 1762 Kaiserin von Russland. Frau Peters III. Sie entmachtete ihren Mann und ließ sich zur Kaiserin ausrufen. Sie förderte die Ansiedlung von Ausländern in Russland. Russlands Machtbereich konnte sie so weit ausbauen, dass nach zwei Kriegen gegen die Türken Russland über einen Zugang zum Schwarzen Meer verfügte. Außerdem wirkte sie an den drei Teilungen Polens entschieden mit und führte 1788 Krieg gegen die Schweden.

Katharina II. im Ornat der regierenden Kaiserin , Ölgemälde von Vigilius Eriksen 1778/1779

Grand Vizier: Der Großsultan, bei dem der Freiherr von Münchhausen im Fünften See-Abenteuer zu Gast ist, lässt sich als Abdülhamid I. (1725-1789), Sultan des Osmanischen Reiches und 106. Kalif des Islam, identifizieren; seine Regierungszeit war geprägt durch die Bedrohung durch die Russen und andere Mächte, wirtschaftliche Krisen, innere Unruhen und Kriege. Um die Schwäche des Reiches zu überwinden, kam es zu Ansätzen wirtschaftlicher, administrativer und militärischer Reformen. Während der Sultan das eigentliche Regierungshandeln weitgehend seinen Wesiren und Beratern überließ, tat er sich als Bauherr und Förderer öffentlicher Einrichtungen hervor. Zu seiner Zeit bekam der Kalifentitel wieder stärkere Bedeutung.

27. Sultan des Osmanischen Reiches und 106. Kalif des Islam; Abdülhamid I. (1725-1789)

Solĭman II., Sultan der Osmanen 1520–66, geb. 1496, war

der Sohn und Nachfolger Selim I. Bei den Türken hat er den Beinamen: Kanuni,

d.h. der Gesetzgeber, bei den christlichen Geschichtschreibern heißt er der

Prachtliebende. Er war ein kluger, gerechter und kriegerischer Fürst. Er

stellte die Ordnung im Reiche her, bezwang 1522 nach einem hartnäckigen

Kampfe die von den Johanniterrittern vertheidigte Insel Rhodus, schlug in

Ungarn 1526 die siegreiche Schlacht bei Mohatsch, eroberte 1529 Ofen und

belagerte Wien, von wo er sich jedoch nach 20 hartnäckigen Stürmen und einem

Verluste von 80,000 Mann wieder zurückziehen mußte. Auch im Orient breitete

er seine Herrschaft aus, erlitt aber 1565 abermals großen Verlust vor Malta.

Nachdem er 1566 noch die Insel Chio eingenommen, rückte er aufs Neue in

Ungarn ein und starb bei Belagerung der Festung Szigeth, welche vier Tage

nach seinem Tode den Türken in die Hände fiel. Er war eifrig besorgt, den

Wohlstand seiner Unterthanen zu befördern, brachte Ordnung in die

Verwaltung, war ein Feind aller Verschwendung und befleckte seinen Ruhm nur

durch die unbeugsame Hartnäckigkeit seines Willens, durch seine

Eroberungssucht und durch Grausamkeit.

Zeno.org, Brockhaus 1837.

Solĭman II., Sultan der Osmanen 1520–66, geb. 1496.

Prince Potemkin:

Grigori Alexandrowitsch Potjomkin (deutsch auch Gregor Alexandrowitsch

Potemkin; 1739-1791) war ein russischer Fürst,

Feldmarschall sowie Vertrauter und Liebhaber der russischen Kaiserin

Katharina der Großen. Er war auch Reichsfürst im Heiligen Römischen Reich.

Wikipedia

Queen of France:

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (1755-1793) war die letzte Königin von

Frankreich vor der Französischen Revolution. Sie wurde als Erzherzogin von

Österreich geboren und war das vorletzte Kind und jüngste Tochter von Kaiserin

Maria Theresia und Kaiser Franz I. Sie wurde im Mai 1770 im Alter von 14 Jahren

nach ihrer Heirat mit Louis-Auguste, dem Erben des französischen Throns,

Dauphine von Frankreich. Am 10. Mai 1774 bestieg ihr Mann als Ludwig XVI. den

Thron und sie wurde Königin.

Wikipedia

Marie Antoinette, Porträt von Gautier-Dagoty, 1775, Schloss Versailles

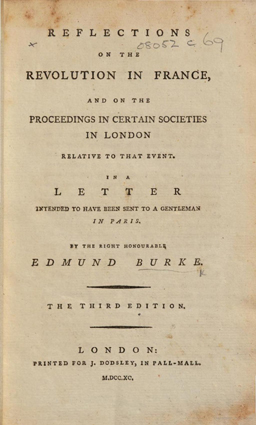

pamphlet written by Mr. Burke: Edmund Burke (1729-1797) war ein irisch-britischer Schriftsteller, früher Theoretiker der philosophischen Disziplin der Ästhetik, Staatsphilosoph und Politiker in der Zeit der Aufklärung. Er gilt als geistiger Vater des Konservatismus.

Werkstatt von Joshua Reynolds: Edmund Burke. Öl auf Leinwand, um 1769.

Burke hielt es für unvorstellbar, dass eine Regierung von „500 Advokaten und Dorfpfarrern“ dem Willen einer Masse von 24 Millionen und deren recht verschieden gearteten Belangen gerecht werden könne. Die damaligen Machthaber betrachtete er mit Geringschätzung und bezeichnete sie als untragbar, aber immerhin als aufgewertet bezeichnet durch die abgefallenen Angehörigen höherer Stände, die nun an der Spitze dieses Kreises stehen. Die naturgegebenen Verhältnisse, und damit Recht und Ordnung, sind für ihn einer ochlokratischen Ordnung zum Opfer gefallen, und schließlich bleibe auch die Vernichtung des Eigentums unvermeidlich.

Bei dem Versuch der siegreichen Vordenker der Aufklärung, Frankreich in eine demokratische Form zu pressen, sei es zerstückelt worden. Für höchst bedenklich hält Burke die Einteilung in 83 Départements, die er als Republiken aufgefasst wissen will, die ihrerseits autonome Bestrebungen hegen und kaum von einer Zentralherrschaft unterworfen werden und auch nicht zugunsten der Republik von Paris verordnete Einschränkungen in Kauf nehmen wollten. Dabei werde die Republik Paris nichts unversucht lassen, um ihren Despotismus erstarken zu lassen.

Burke stand mit seiner skeptischen, den Rationalismus in der Politik ablehnenden

Haltung in scharfem Gegensatz zu Jean-Jacques Rousseau, auf den sich die

Vordenker der Französischen Revolution beriefen. Der Versuch, die Grundsätze des

gesellschaftlichen Zusammenlebens a priori festzulegen, müsse an der objektiven

Realität und der menschlichen Natur scheitern, so Burke.

Wikipedia

REFLECTIONS ON THE REVOLUTION IN FRANCE, AND ON THE PROCEEDINGS IN CERTAIN SOCIETIES IN LONDON RELATIVE TO THAT EVENT. BY EDMUND BURKE. THE THIRD EDITION. LONDON: M.DCC.CX.

Zurück

zur vorigen Seite

![]() Nächste Seite

Nächste Seite

![]()